Use of Mother Tongue in Foreign Language Teaching: True or False?

- ÜtopÇa

- May 1, 2023

- 7 min read

One of my memories of language teaching is always fresh in my memory and comes to mind whenever I teach English to first graders. I was enthusiastically listing the classroom rules in English to a first-year student and talked nonstop for 2-3 minutes. I was going to continue when I found my student imitating me in anger with "blablablablabla" and interrupted my speech. At that moment, I had enlightenment. Everything I said to this boy sounded "blablablablabla" at that moment. The words I said had no meaning to him. Even if I spoke for another 3 minutes, he would not understand me. And at that moment, I realized that the stereotypes of "never speak your mother tongue while teaching English", and "the child will never speak to you again in English once she/he hears you speak Turkish" do not work in practice anymore.

The use of mother tongue (L1) in foreign language (FL) education is a highly controversial issue.

According to the language acquisition theory, some educators believe in constant and intense exposure to the target language, while some educators and even the studies conducted in the last ten years argue that the mother tongue facilitates the learning process for both the teacher and the learner.

In the first years of my teaching, I was afraid to speak Turkish, which is my mother tongue, like it was a sin, as we were taught in our classes in undergraduate programs. However, over the years, when I use only the target language with some of my students, especially those who were afraid of making mistakes, went out of their comfort zone very hard, tried to develop self-confidence skills, and had difficulties in learning a new language, these students' motivation to learn a language, their self-confidence, and their focus decrease drastically. I even observed that there was a regression in their learning. Observing these students and at the time that I saw that they did not understand, going next to them, repeating the instruction in my mother tongue, or asking them how they were when I caught them alone from time to time, relieved them and strengthened the bond between us. It is very pleasing to see that these experiences I had had a place in the research of Swain and Lapkin (2000) and Macaro (2000).

Which way should we choose when teaching a foreign language (FL)?

As a language teacher, I recommend making some clear distinctions before deciding which path to take.

First of all, the age range of your student audience is very important. According to the two language acquisition theories in the field (critical period and brain plasticity), the first threshold is 5 years old, and the second threshold is 12 (pre-adolescence). After these ages, it is very difficult to "acquire" the language, that is, to learn the language the way a baby learns their mother tongue (L1).

The main goal in "language acquisition" is to adopt the language placed on top of the mother tongue (L1) as a second language (L2). The brain thinks, speaks, reads, and writes the acquired language in a close manner to the mother tongue (L1) at a later age. Therefore, if your student is less than 12 years old, you can go for language acquisition.

So what does this mean? Intense repetition as much as possible, condensed input (series, movies, cartoons, songs, dialogs in the target language), adapting the language you will teach to every moment of your life, instilling language through body language, imitation, exploratory learning, and play. At this point, I suggest you avoid using your native language(L1). However, as I mentioned at the beginning of the article, if you have exceptional students, reluctance to learn, hesitancy, or loss of motivation, you can use L1 depending on the dose.

If your learners are children over the age of 12, adolescents, or even adults, it will take a huge toll on both you and your students to embrace teaching and not "acquire" the language. Because after this point, the language you will give will no longer be your student's second language (L2), but their foreign language (FL).

After determining the age and language education approach, the second question is,

To what extent and how will you use the mother tongue (L1) during teaching?

Although this question varies according to the teacher, student profile, and the language target determined, it can be summarized under several main headings based on the research:

Using it by Paying Attention to Its Main Function and Social Function

Hall & Cook (2013) discovered in their research that teachers speak their mother tongue in class only for the purpose of teaching the language. In other words, teachers use their mother tongue when teaching grammar structure or vocabulary, or when determining whether students have grasped the subject matter. Interestingly, contrary to what we have been taught, there is no evidence in the field that using the mother tongue with this function interferes with language learning. The secondary function, where L1 is often used in the classroom, is to give instructions or manage the class.

I realized that when I bring the suffix "-cim, -cim", which shows sincerity in Turkish, to my students in my classes, I draw their attention, the emotional bond established between us is strengthened, and they strive to fulfill what I expect from them unconditionally. Even these small additions to the target language that you transfer from your mother tongue can have a big impact.

Applying the Sandwich Technique (a mother tongue word between the two extreme foreign language sentences)

The main language you speak in the classroom should definitely be the target language. You can use one-word explanations in your mother tongue which you cannot show with your body language, where the meaning is complex and the content of the task you are giving is more important than the instruction itself. For example; in the "match the words with the pictures on your own" directive, say "eşleştir" in your own language after highlighting the word "match" ; and say "kendi kendine" after emphasizing the phrase "on your own".

Using Bilingual Images

Another effective method in which the mother tongue plays a role in foreign language teaching is to use of visuals. Such as posters in your school or classroom where the content is more important than the language (class rules, help statements, headlines, etc.), descriptions of your classroom work, or flashcards of your favorite instructions.

Getting Help from Other Students as a Translator

You don't have to be the only native speaker. You can ask a student who you think speaks fluently and correctly in the target language to retransmit an instruction or a speech whose content you think is important in their mother tongue.

Creating "Mother Tongue Times"

Constant exposure to a foreign language, especially at a young age, requires constant high focus. This, in turn, triggers fatigue and a feeling of boredom. Surprise your students when you feel these moments. Give 2-3 minutes of "L1 Time" depending on the course of your lesson plan. This brief return to the mother tongue will increase your students' focus, and lead to a moment of a shake-up and perceptual relaxation.

Shut the Eyes to L1 in Group Studies

In group work, it is an excellent example of a skill for students to experience the target language themselves and establish a dialogue among themselves. However, as the subjects get more difficult, it becomes difficult to reach a common decision and produce a product in group work. Doing this in a foreign language also affects the efficiency of the process. If speaking or listening is not the skill you want to gain in group work, you can let them practice the language of communication in their mother tongue. In fact, I witnessed such moments in this type of group work that, thanks to peer learning and language transition, my student was able to teach the words that I could not teach to my student, using the right pronunciation and the right content.

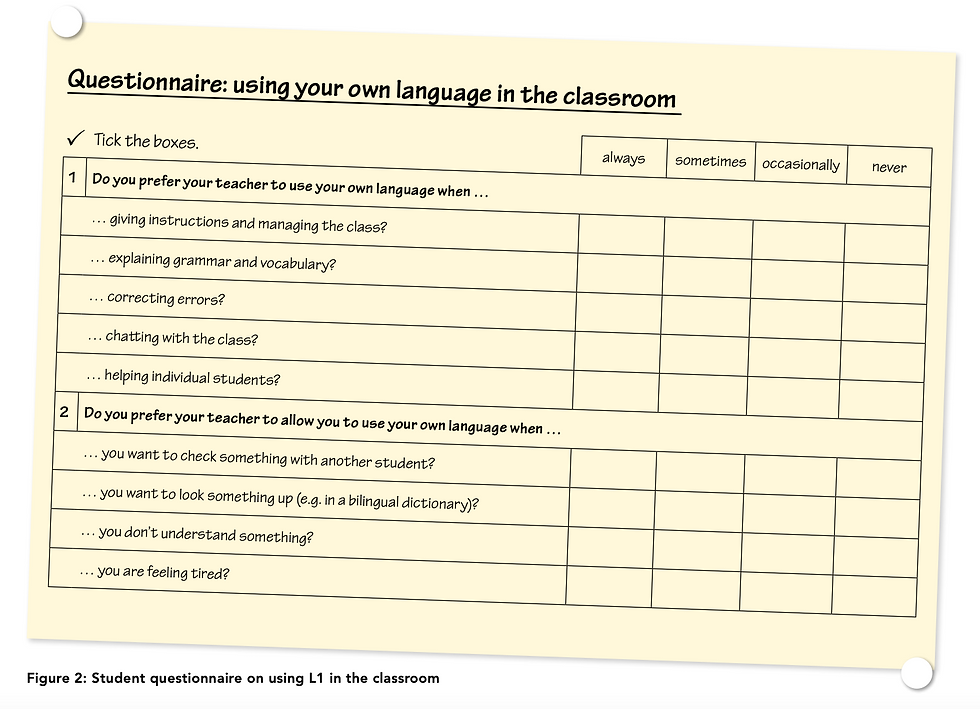

In short, it is not a sin to use the mother tongue when teaching a foreign language, dear language teachers. In fact, it is now a proven fact in the literature that it contributes to language learning, as it will of course vary depending on how much you use it and for what purpose. Below I share the links to the research on which this fact is based. In fact, if you wish, you can measure the expectations of your students by applying the "Survey on Use of Native Language in the Classroom" mentioned in Cambrigde's article on this subject.

When I discovered the healing and unifying power of the mother tongue in foreign language teaching, I would like to end my article with another memory that breaks the stereotypes engraved in our minds:

My students who didn't feel safe speaking English heard me speak Turkish, and I also had students who spoke English fluently and accurately, who heard me speaking Turkish even though I was hiding. To them, when I ask the question,

"Would you like me to speak to you in English or Turkish?"

the answer is always the same without any exceptions,

"English"

In other words, whether you speak your mother tongue or a foreign language, once the student has accepted you as the teacher of the target language, he or she will always want to hear the target language from you. To sum up, don't worry, trust your students and teacher's intuition, realize the need, and don't limit yourself or your student with the language you want to teach, just focus on the message you want to give.

Resources:

Hall, G. & Cook, G. (2013). Own-language Use in ELT: Exploring global practices and attitudes. London: British Council. 31st December 2018.

Macaro, E. (2000). Issues in target language teaching. In Field, K. (Ed.) Issues in Modern Foreign Languages Teaching. Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge: pp. 171–189.

Swain, M. and Lapkin, S. (2000). Task-based second language learning: the use of the first language. Language Teaching Research, 4(3): pp. 251–274.

https://www.cambridge.org/ai/files/6315/7488/4318/CambridgePapersInELT_UseOfL1_2019_ONLINE-2.pdf

Comments